You are here

Position Statement 41: Early Identification of Mental Health Issues in Young People

Policy

Early identification, accurate diagnosis and effective treatment of mental health and substance use conditions[1] can alleviate enormous suffering for young people and their families dealing with behavioral health challenges. Providing early care can help young people to more quickly recover and benefit from their education, to develop positive relationships, to gain access to employment, and ultimately to lead more meaningful and productive lives.

Thus, Mental Health America (MHA) supports universal screening for potential mental health problems for the same reasons and in the same settings that screening has long been mandated for potential physical health problems, like vision and hearing. MHA believes that early identification of mental health and substance use issues should occur where and when young people are mostly likely to present concerns, such as in school. In addition to schools, primary health care providers and other community leaders should be given the tools and supports necessary to identify signs of mental health or substance use issues at the earliest possible time. This position is endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics[2] and (for depression in youth over age 11) the United States Preventive Services Task Force.[3] Doing so will reduce the likelihood and consequences of delaying care.

Community outreach and education are necessary to identify problems in order to refer youth to additional comprehensive assessment and to the care they need to cope with mental health and substance use challenges. Funding and promotion of community outreach and education to identify early signs of mental health and substance use conditions can arm parents, teachers, friends, spiritual leaders, mentors, and community leaders with knowledge, skills, and resources for identifying and referring youth into necessary care. Additional research is needed to identify the best curricula for community-wide education that will most likely lead to proper referral and reduce the severity and duration of mental illness and addiction.

Whenever warning signs are observed, resources should be available to parents or guardians to access comprehensive mental health and substance use evaluations and services needed to promote recovery.[4] Access to adequate care can reduce barriers to learning and improve educational, behavioral and health outcomes for our youth. The best services promote collaboration among all of the people available to help, including families, educators, child welfare case workers, health insurers, and community mental health and substance use treatment providers. Barriers should be reduced and incentives created to ensure increase collaboration across systems and funding sources.

Background

Mental health problems affect one in five young people at any given time, and about two-thirds of all young people with mental health problems are not getting the help they need. [5] [6] Research shows that early intervention can prevent significant mental health problems from developing.[7] Epidemiological research confirms the relationship between mental health issues and suicide or self-mutilation, substance abuse, suspension, dropping out, expulsion and involvement with the juvenile justice system.[8] The research also shows that effective treatment can reduce the risk of such consequences.[9] [10]

The 2002 New Freedom Commission on Mental Health proposed as a goal that: "In a transformed mental health system, the early detection of mental health problems in children and adults - - through routine and comprehensive testing and screening - - will be an expected and typical occurrence."

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention[11] and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration[12] conduct comprehensive research on the prevalence rates of mental health and substance use issues as well as the barriers to accessing care. Key recent findings include:

- Millions of American young people live with depression, anxiety, psychosis, attention problems, autism spectrum disorders, and a host of other mental and behavioral health issues. Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) was the most prevalent current diagnosis among children and youth aged 3–17 years.[13]

- The number of young people with a mental disorder increased with age, with the exception of autism spectrum disorders, which was highest among 6 to 11 year old children.

- Boys were more likely than girls to have attention, behavioral or conduct problems, autism spectrum disorders, anxiety, and cigarette dependence.

- Adolescent boys aged 12–17 years were more likely than girls to die by suicide.

- Adolescent girls were more likely than boys to have depression or an alcohol use disorder.

Young people aged 3-17 years had:

- Attention problems (6.8%)

- Behavioral or conduct problems (3.5%)

- Anxiety (3.0%)

- Depression (2.1%)

- Autism spectrum disorders (1.1%)

Adolescents aged 12–17 years had:

- Illicit drug or alcohol dependence or abuse in the past year (5.5%)

- Major depression (11%);

- Severe depression[14] (7%)

- Cigarette dependence in the past month (2.8%)

- Bipolar disorder (3%)[15]

- Eating disorder (2.7%)[16]

Recent research on early signs of psychotic illnesses like schizophrenia identified that 100,000 adolescents and young adults experience first episode psychosis each year.[17]

And suicide, which can result from the interaction of mental disorders and other factors, was the second leading cause of death among adolescents aged 12–17 years in 2013.[18]

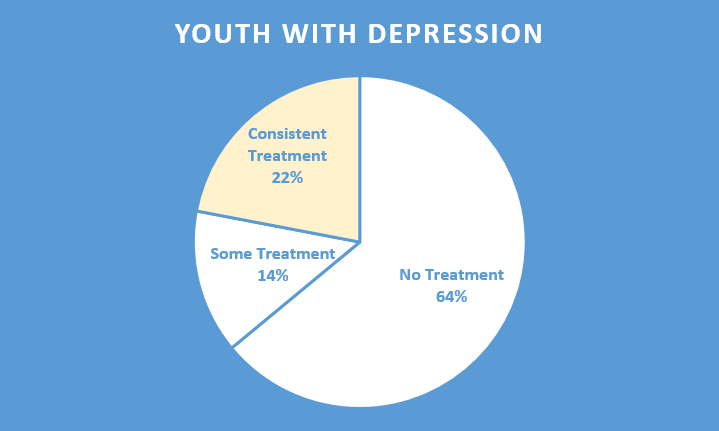

Evaluating access to care, 64% of youth with major depression did not receive any mental health treatment, while only 22% receive any consistent treatment (7+ visits annually).[19] Despite passage of the Affordable Care Act and mental health parity, 8% of youth do not have any mental health insurance coverage.[20]

Research provides us with an understanding of the prevalence of mental health and substance use problems among youth. The importance of identifying and targeting problems in young people both before and after adolescence is strengthened by the fact that 50 % of mental health problems present themselves before the age of 14 – more often than not tied to brain changes that occur during puberty. [21] [22]

Screening

Universal screening for mental health problems is necessary to reach youth who otherwise would fall through cracks. Pediatricians, primary care physicians and other health care providers are indispensable adjuncts to school-based assessment in identifying signs of mental health problems because they routinely see young people and their families and because confidentiality is assured. Even if specialized mental health treatment is not readily available, the support of a primary care physician and staff can go a long way in providing support and getting people on a path towards recovery. The Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment (EPSDT) provisions are among the most specific in the Social Security Act,[23] but they cover only Medicaid recipients and have not always been fully implemented. Research has provided reliable, culturally and linguistically competent early identification and diagnostic tools.[24] [25] Increasingly, models of collaborative care provide primary care providers with the additional support necessary to provide comprehensive treatment in primary care that meet the individualized needs of the child and family, available on a nondiscriminatory basis.[26] [27] [28]

Although schools are required to identify all mental and other health impediments to learning under the federal Rehabilitation Act and Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act, including mental health issues, screening for emotional or behavioral difficulties in schools has sometimes been controversial and politicized. The concerns regarding school-based screening include the potential conflict between the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act,[29] which governs most school records, and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA),[30] which governs all medical and mental health records. There are concerns about how to protect confidentiality of mental health and substance use evaluations in an educational setting, and there are concerns about how best to follow up with parents or guardians by school personnel to ensure linkage to follow up care. In addition, issues of possible cultural and racial bias are a significant concern among people of color. The development of reliable and culturally and linguistically appropriate screening tools remains an urgent priority.[31]

MHA acknowledges these challenges of school-based mental health screening. However, with appropriate safeguards, MHA supports well-designed pre-school-based and school-based screening programs. Because teachers, school psychologists, social workers and other counselors have extended contact with children on a daily basis, they are often in the best position to recognize early patterns of behavior that pose a risk for a child’s academic, social, emotional or behavioral functioning. While teachers and other school administrators are not and should not become diagnosticians, their candid communication with the family is vital in promoting students' well-being, including their mental health. Where any health problems are noted, their concerns should be shared with the parents or guardian in a timely manner, and parents and guardians should be counseled to see their primary care physician or a mental health professional concerning their child's need for mental or other health care.

Mental health and substance use problems should be treated no differently than other health-related concerns. School personnel should be trained to recognize the early warning signs of mental health and substance use conditions and to know the appropriate actions to take in notifying parents or guardians and in protecting the rights and privacy of young people.

In so doing, it is important to maintain strict confidentiality in accordance with HIPAA, communicating in a clear and culturally competent manner, and involving the parents or guardians in respectful shared decision-making.

Several states have sought to ban mental health screening in schools. MHA opposes such legislation because it compromises the responsibilities of the schools under federal law to provide an education to all young people, regardless of disability, compromises the schools' obligation to identify and address significant impediments to learning of all kinds, discriminates against young people with emotional or behavioral difficulties, and risks constraining free communication by teachers and counselors to parents and guardians, which is essential to early identification and effective treatment of mental health and substance use conditions.

Outreach and education

Promoting community education has been identified as a goal in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Healthy People 2020 initiative. The initiative is significant in recognizing that education programs play a key role in preventing disease, improving health, and enhancing quality of life and includes educating communities on mental illness, behavioral health, substance use, tobacco use, and injury prevention.[32] Public education is needed to assure that parents, friends, teachers, school officials, primary care physicians and other health care providers can identify the early signs of mental health and substance use problems so that young people can receive the help that they need in a timely manner. With long-term investment among stakeholders at various levels in communities, programs related to mental health education have been shown to reduce rates of suicide[33], increase student knowledge of depression[34], and increase in help seeking behaviors.[35] Research testing new models for community health education has demonstrated the effectiveness of increased proactive engagement among key stakeholders to improve youth mental health.[36] Specifically, providing effective community-based outreach and education increases the likelihood of effective referral from a community member (like a teacher or spiritual leader) to supportive services that provide additional comprehensive assessment and therapeutic services. Teachers/educators need to learn de-escalation techniques and skills to decrease crisis situations leading to suspensions of young people with mental health conditions.

In order to prioritize community education, additional funding is needed. Despite the research on the benefits of community education for early identification of mental health problems, no current funding is available for comprehensive community-based education on the early warning signs of mental illness, early brief intervention, and linkage and referrals to treatment. New research has provided a starting point for promising programs in community-based education in mental health, and more research and research funding is needed to identify specific curricula and outreach activities that can promote early identification and effective linkage to appropriate treatment and supports.

Linkage

For early identification to have any value, public and private resources must be available to assure effective treatment. Reliable early identification of health problems in schools and primary care settings and effective, nondiscriminatory treatment can help to address a young person’s needs before they lead to greater academic or social problems, including suicide or self-injury, substance use, school failure, suspension, dropping out, or expulsion, or involvement with the juvenile justice system.

In January, 2016, the U.S. Department of Education with and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services called Healthy Students, Promising Futures.[37] The toolkit provided five high impact opportunities for collaboration between health care and schools: 1) help eligible students and family members enroll in health insurance, 2) provide and expand reimbursable health services in schools, 3) provide or expand services that support at-risk students including through Medicaid-funded case management, 4) promote health school practices through nutrition, physical activity, and health education, and 5) build local partnerships and participate in community needs assessments. Implementing the five opportunities would make significant change towards reducing the burden for teachers and parents to coordinate services, improve children’s outcomes, and reduce the need for additional special education services.

Call to Action

- As part of parity, private and public health insurers should sufficiently reimburse for psychoeducation, screening, brief intervention, referral, and follow-up in the same way that primary health care prevention is reimbursed;

- EPSDT compliance, i.e. rates of screening, brief intervention, referral, and follow-up, should be publically reported and failures to comply should be routinely investigated. Consent decrees have been entered against several states that were not meeting their EPSDT obligations.[38]

- States should prohibit the grade retention, suspension or expulsion of a child unless the child has received appropriate mental health screening.

- As part of the Every Student Succeeds Act implementation, school districts should identify current programming that supports identification and treatment for mental health and coordinate and augment these efforts to ensure that they fully meet the social and emotional needs of the students, as revealed by the district’s needs assessment. Getting and protecting required funding for screening and treatment is essential as schools face cutbacks.[39] States should facilitate the process of health clinics opening branch sites inside of schools to supplement the school-based health center movement.

- The Medicare coverage determination and evaluation by CMS should be revised in light of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force update on depression screening, so that it covers screening, brief intervention, referral, and follow-up, not only screening when supports are in place;

- The Department of Education and the Department of Health and Human Services should provide additional technical assistance for its toolkit, Healthy Students, Promising Futures (cited above), and states should provide guidance on how to implement the recommendations;

- The Office of Civil Rights of the Department of Education should audit states for compliance with the child finding provision of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, which requires states to identify children with disabilities.

- Additional federal and state funding can support research and implementation of community based education on early warning signs and early brief strategies for prevention and early intervention.

- Affiliates can offer information and training to pediatricians and other primary care providers about early identification and screening.

- Affiliates can offer training sessions to parents and school personnel on appropriate early identification of children at risk, alternatives for getting help, and effective communication by school personnel.

- Affiliates can support federal efforts in promoting state and local entities in adopting the recommendations from Healthy Students, Promising Futures.

- Affiliates and advocates should encourage early identification and early intervention and should work to defeat any legislation that gets in the way of candid discussion of mental health and substance use issues.

Effective Period

Mental Health America Board of Directors adopted this policy on September 18, 2016. It will remain in effect for a period of five (5) years and is reviewed as required by the Mental Health America Public Policy Committee

Expiration Date: December 31, 2021

[1] The term “mental health or substance use conditions” as used in this policy statement is intended to include the federal term “emotional or behavioral disturbance.”

[2] AAP Schedule of Screenings and Assessments for Well-Child Assessments (February 24, 2014), https://www.aap.org/en-us/about-the-aap/aap-press-room/pages/AAP-Updates-Schedule-of-Screening-and-Assessments-for-Well-Child-Visits.aspx?nfstatus=401&nftoken=00000000-0000-0000-0000-000000000000&nfstatusdescription=ERROR:+No+local+token

[3] PSPSTF Depression in Children and Adolescents: Screening (February 2016), http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/depression-in-children-and-adolescents-screening1

[4] Early intervention in response to identified mental health or substance use conditions is distinguished from mental health and sobriety promotion and prevention of mental health and substance use disorders, which are addressed separately in MHA Position Statement 48. http://www.nmha.org/go/about-us/what-we-believe/position-statements/p-48-prevention-in-young-people/position-statement-48-prevention-of-mental-health-and-substance-use-disorders-in-young-people

[5] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Mental Health Surveillance among Children – United States, 2005—2011, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 62:1-35 (2013), http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/su6202a1.htm.

[6] Merikangas, K.R., He, J,P., Burstein, M.E., Swendsen, J., Avenevoli, S., Case, B., Georgiades, K., Heaton, L., Swanson, S. & Olfson, M.. “Service Utilization for Lifetime Mental Disorders in U.S. Adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A),” Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 50(1):32-45 (2011).

[7] O'Connell, M. E., Boat, T., & Warner, K. E. (Eds.), Preventing Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders among Young People: Progress and Possibilities, National Academies Press (2009).

[8] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Suicide: Facts at a Glance. (2015), http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/suicide-datasheet-a.pdf.

[9] U.S. Interagency Working Group of Youth Programs (IWGYP). How Mental Health Disorders Affect Youth, http://youth.gov/youth-topics/youth-mental-health/how-mental-health-disorders-affect-youth.

[10] O'Connell, M.E., Boat, T. and Warner, K.E., eds. Preventing Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders among Young People: Progress and Possibilities, op. cit.

[11] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Mental Health Surveillance among Children – United States, 2005—2011, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, op. cit.

[12] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Comparison of 2012-2013 and 2013-2014 Population Percentages, http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHsaeShortTermCHG2014/NSDUHsaeShortTermCHG2014.pdf)

[13] This may be misleading, since ADHD is often used to diagnose attention problems that are best diagnosed as other mental health conditions. To learn more, visit: http://childmind.org/article/the-most-common-misdiagnoses-in-children/.

[14] i.e., significant depression below the level needed to confirm a major depression diagnosis.

[15] National Institute of Mental Health, Bipolar Disorder among Children, http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/prevalence/bipolar-disorder-among-children.shtml

[16] National Institute of Mental Health, Eating Disorders among Children, http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/prevalence/eating-disorders-among-children.shtml

[17]National Institute of Mental Health, RAISE Questions and Answers, http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/schizophrenia/raise/raise-questions-and-answers.shtml

[18] Heron, M., "Deaths:Lleading Causes for 2013." National Vital Statistics Reports, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System 65(2):1-96 (2016), http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr65/nvsr65_02.pdf

[19] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2013, http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHresultsPDFWHTML2013/Web/NSDUHresults2013.pdf

[20] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2013, op. cit.

[21] Kessler, R.C., Chiu, W.T., Demler, O., Merikangas, K.R. & Walters, E.E., “Prevalence, Severity, and Comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication,” Arch Gen Psychiatry. 62(6):617-27 (2005).

[22] Paus, T., Keshavan, M., & Giedd, J. N., “Why Do Many Psychiatric Disorders Emerge During Adolescence?” Nature Reviews Neuroscience 9(12): 947-957 (2008).

[23] See 42 U.S.C.§§ 1396a(a)(10)(A), 1396a(a)(43), 1396d(a)(4)(B), 1396d(r).

[24] Wulsin, L., Somoza, E. & Heck, J., “The Feasibility of Using the Spanish PHQ-9 to Screen for Depression in Primary Care in Honduras,” J Clin Psychiatry 4(5):191-195 (2002).

[25] García-Campayo, J., Zamorano, E., Ruiz, M.A., Pardo, A., Pérez-Páramo, M., López-Gómez, V., Freire, O. & Rejas, J., “Cultural Adaptation into Spanish of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) Scale as a Screening Tool,” Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 8(1):1 (2010).

[26] Connor, D.F., McLaughlin, T.J., Jeffers-Terry, M., O’Brien, W.H., Stille, C.J., Young, L.M. & Antonelli, R.C., “Targeted Child Psychiatric Services: a New Model of Pediatric Primary Clinician—Child Psychiatry Collaborative Care,” Clinical Pediatrics 45(5):423-434 (2006).

[27] Zatzick, D., Russo, J., Lord, S.P., Varley, C., Wang, J., Berliner, L., Jurkovich, G., Whiteside, L.K., O’Connor, S. & Rivara, F.P., “Collaborative care intervention targeting violence risk behaviors, substance use, and posttraumatic stress and depressive symptoms in injured adolescents: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatrics 168(6):532-539 (2014).

[28] Garner, A.S., Shonkoff, J.P., Siegel, B.S., Dobbins, M.I., Earls, M.F., McGuinn, L., Pascoe, J. & Wood, D.L., “Early childhood adversity, toxic stress, and the role of the pediatrician: translating developmental science into lifelong health,” Pediatrics, 129(1):e224-e231 (2012).

[29] 20 U.S.C. § 1232g; 34 CFR Part 99

[30] P.L. 104-191, 110 Stat.1936 (1996), 29 U.S.C. §1181, 42 U.S.C. §1320, 1395, and associated rulemaking by the Department of Health and Human Services, 45 C.F.R. §§160-164. HIPAA enforcement was substantially strengthened by the passage of the HITECH Act, Public Law 111–5, 123 Stat. 115 (2009), and sections within 45 CFR part 160 finalized in 2013 that relate to the authority of the Secretary of the HHS to impose civil penalties under Section 1176 of the Social Security Act, 42 U.S.C. 1320d–5.

[31] Feeney-Kettler, K.A., Kratochwill, T.R., Kaiser, A.P., Hemmeter, M.L. & Kettler, R. J., “Screening Young Children's Risk for Mental Health Problems: A Review of Four Measures,” Assessment for Effective Intervention 35(4):218-230 (2010).

[32] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Healthy People 2020, Education and Community-Based Programs. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/educational-and-community-based-programs

[33] Fountoulakis, K.N., Gonda, X., & Rihmer, Z., "Suicide Prevention Programs Through Community Intervention." Journal of Affective Disorders 130(1):10-16 (2011).

[34] Swartz, K.L., Kastelic, E.A., Hess, S.G., Cox, T.S., Gonzales, L.C., Mink, S.P. and DePaulo, J.R., “The Effectiveness of a School-Based Adolescent Depression Education Program,” Health Education & Behavior 37(1):11-22 (2010).

[35] Ruble, A.E., Leon, P.J., Gilley-Hensley, L., Hess, S.G. and Swartz, K.L., “Depression Knowledge in High School Students: Effectiveness of the Adolescent Depression Awareness Program,” Journal of Affective Disorders 150(3):1025-1030 (2013).

[36] Ruff, A., McFarlane, W., Downing, D., Cook W., & Woodberry, K. A., “Community Outreach and Education Model for Early Identification of Mental Illness in Young People,” Adolescent Psychiatry, 2(2):140-145 (2012). http://benthamscience.com/journals/adolescent-psychiatry/volume/2/issue/2/page/140/

[37] Healthy Students, Promising Futures, State and Local Action Steps and Practices to Improve School Based Health, Department of Health and Human Services and Department of Education (Jan 2016), http://www2.ed.gov/admins/lead/safety/healthy-students/toolkit.pdf

[38] Over the years, states have not adhered to the ESPTD mandate, and litigation has resulted. EPSDT establishes a broad scope of benefits—all the services listed within the Social Security Act at 42 U.S.C. § 1396d(a)—and a uniform medical necessity definition—services needed to “correct or ameliorate” the child’s physical or mental conditions. 42 U.S.C. §1396d(r)(5). Advocates are citing these broad treatment requirements to obtain coverage for a range of services that children need to live at home and in the community, including screening, rehabilitative services, case management, home health care, and personal care services. See, generally, National Health Law Program, Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis and Treatment (EPSDT) (October 15, 2013), http://www.healthlaw.org/issues/child-and-adolescent-health/epsdt/health-advocate-epsdt#.V6JEVjUe48I

[39] The Minnesota Association for Children’s Mental Health has prepared two exemplary toolkits for teachers: Unlocking the Mysteries of Children’s Mental Health: An Introduction for Future Teachers, Minnesota Association for Children’s Mental Health, St. Paul, MN (Rev. Ed. 2004.) and A Teacher’s Guide to Children’s Mental Health, Minnesota Association for Children’s Mental Health, St. Paul, MN (2002). See http://www.macmh.org/macmh-publications/

this page