You are here

Position Statement 27: Standards For Management of and Access to Consumer Information

Summary

Mental Health America (MHA) recommends that health care providers, consumers, families and other caregivers become familiar with the Guidance described in this position statement that clarifies the standards of confidentiality incorporated in the Health Information Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) concerning mental health and substance use treatment. The Guidance shows how health care providers can:

- Communicate with a consumer’s family members, friends, or others involved in the consumer’s care;

- Communicate with family members when the consumer is an adult;

- Communicate with the parent of a minor;

- Consider the consumer’s capacity to agree or object to the sharing of their information;

- Involve a consumer’s family members, friends, or others in dealing with failures to adhere to medication or other therapy;

- Listen to family members about their loved ones receiving mental health treatment; and

- Communicate with family members, law enforcement, or others when the consumer presents a serious and imminent threat of harm to self or others.

Advocates should ensure that state laws and local providers balance confidentiality interests with respect to:

- Medical Emergencies

- The Rights of Minors

- Court Orders

- Psychiatric Advance Directives

- Super-Confidential Information

- Duty to Warn

- HIPAA Enforcement

Policy

Mental Health America (MHA) supports ongoing clarification of the standards of confidentiality incorporated in the Health Information Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA)[1] in a manner that provides consumers with maximum protection of their privacy while enhancing the quality and coordination of consumer care and alleviating unreasonable burdens on consumers, families, clinicians and health care providers.

MHA recommends that HIPAA, a complex law and with extensive implementing regulations,[2] be read in conjunction with the United States Department of Health and Human Services’ Office for Civil Rights (OCR)’s 2014 Guidance concerning HIPAA implementation.[3] The Guidance, portions of which are quoted in the Background section of this position statement, clarifies the most critical questions that must be resolved in implementing HIPAA in a mental health or substance use context.[4] Despite widespread concern that HIPAA may interfere with sharing of information essential to good mental health and substance use disorder care,[5] the Guidance shows how health care providers can:

- Communicate with a consumer’s family members, friends, or others involved in the consumer’s care;

- Communicate with family members when the consumer is an adult;

- Communicate with the parent of a minor;

- Consider the consumer’s capacity to agree or object to the sharing of their information;

- Involve a consumer’s family members, friends, or others in dealing with failures to adhere to medication or other therapy;

- Listen to family members about their loved ones receiving mental health treatment; and

- Communicate with family members, law enforcement, or others when the consumer presents a serious and imminent threat of harm to self or others.

In addition, the Guidance provides clarification of related issues, such as notification of law enforcement, the heightened protections afforded to psychotherapy notes by HIPAA, a parent’s right to access the protected health information of a minor child as the child’s personal representative, the potential applicability of Federal alcohol and drug abuse confidentiality regulations or state laws that may provide more stringent protections for the information than HIPAA, and the intersection of HIPAA and FERPA in school settings. MHA believes that, in an integrated system, all mental health and substance abuse records should be treated in accordance with a uniform standard applicable to all medical records. Thus, the higher standards for sharing substance abuse records and school medical records should be revised to conform with HIPAA.

MHA advocates that health care providers strictly monitor their compliance with HIPAA privacy standards including the Guidance and take up-to-date, reasonable precautionary measures when engaging in electronic maintenance or transmission of health information. MHA also advocates rapid, fully-informed delivery of services, and accessibility of all information in emergencies.

States should consider further legislation to:

- clarify access to information in emergencies,

- clarify the circumstances under which consent of older minors may be required,

- allow releases of HIPAA protected information to designated health care proxies and in psychiatric advance directives,

- repeal super-confidential information statutes that interfere with integration of care,

- clarify the duty to warn of an identified threat of violence, and

- require that judges considering court disclosure

- weigh the need for disclosure against the potential harm to the consumer and to the clinician-consumer relationship and its impact on the treatment process,

- limit disclosure to information essential to the demonstrated purpose, and

- provide protection against future public scrutiny, such as by sealing court records.

Background: The Law, the Regulations and the Guidance

CONTENTS

· Communications with parents of minors.

· Communications with a consumer’s family members, friends, or other persons whom the consumer has involved in his or her health care or payment for care (such other persons are hereinafter included in the term “friends”).

· What options do family members or friends involved in the care of an adult consumer with mental illness have if they are concerned about the consumer’s mental health and the consumer refuses to agree to let a health care provider share information with them?

· Can family- or friend-provided information be kept confidential?

· If a health care provider knows that a consumer with a serious mental illness has stopped taking a prescribed medication, can the provider tell the consumer’s family members or friends?

· When does mental illness or another mental condition constitute incapacity under HIPAA? For example, what if a consumer who is experiencing temporary psychosis or is intoxicated does not have the capacity to agree or object to a health care provider sharing information with a family member, but the provider believes the disclosure is in the consumer’s best interests?

· Does HIPAA permit a doctor to contact a consumer’s family or law enforcement if the doctor believes that the consumer might hurt herself or someone else?

· The Duty to Warn defined by state laws is recognized by HIPAA.

Consumers, families, clinicians and other health care providers are legitimately concerned that their privacy and confidentiality be protected when mental health and substance use disorder treatment is provided. Automated record keeping, advancements in information system technology, and the growing need for communication among multiple parties to integrate services and accommodate complex administrative arrangements such as managed care have made this task more difficult. With the passage of HIPAA, the associated regulations and the Guidance incorporated in this policy, the most important outstanding issues have been clarified. Now the challenge is to implement the Guidance.

The Guidance, issued by OCR (the Office for Civil Rights, the enforcement arm of the HHS General Counsel’s Office), gives advice rather than codifying a new standard. The issues clarified by the Guidance (Guidance language in bold and in quotes) that are of special concern to consumers of mental health and substance use disorder services and their families are:

1. Communications with parents of minors.

Parents of a minor child have rights to information and custody as defined by state law, and those rights are recognized by HIPAA. HIPAA defers to state law to determine the age of majority and the rights of parents to act for a child in making health care decisions, and thus, the ability of the parent to act as the personal representative of the child for HIPAA purposes. See 45 CFR 164.502(g). The Guidance adds:

“With respect to general treatment situations, a parent, guardian, or other person acting in loco parentis usually is the personal representative of the minor child, and a health care provider is permitted to share consumer information with a consumer’s personal representative under the Privacy Rule. However, section 164.502(g) of the Privacy Rule contains several important exceptions to this general rule. A parent is not treated as a minor child’s personal representative when: (1) State or other law does not require the consent of a parent or other person before a minor can obtain a particular health care service, the minor consents to the health care service, and the minor child has not requested the parent be treated as a personal representative; (2) someone other than the parent is authorized by law to consent to the provision of a particular health service to a minor and provides such consent; or (3) a parent agrees to a confidential relationship between the minor and a health care provider with respect to the health care service. For example, if State law provides an adolescent the right to obtain mental health treatment without parental consent, and the adolescent consents to such treatment, the parent would not be the personal representative of the adolescent with respect to that mental health treatment information.

…[In addition,] the Privacy Rule defers to State or other applicable laws that expressly address the ability of the parent to obtain health information about the minor child. In doing so, the Privacy Rule permits a covered entity to disclose to a parent, or provide the parent with access to, a minor child’s protected health information when and to the extent it is permitted or required by State or other laws (including relevant case law). Likewise, the Privacy Rule prohibits a covered entity from disclosing a minor child’s protected health information to a parent when and to the extent it is prohibited under State or other laws (including relevant case law). See 45 CFR 164.502(g)(3)(ii).”

2. Communications with a consumer’s family members, friends, or other persons whom the consumer has involved in his or her health care or payment for care (such other persons are hereinafter included in the term “friends”).

“Where a consumer is present and has the capacity to make health care decisions, health care providers may communicate with a consumer’s family members [or] friends…, so long as the consumer does not object. See 45 CFR 164.510(b). The provider may ask the consumer’s permission to share relevant information with family members or others, may tell the consumer he or she plans to discuss the information and give them an opportunity to agree or object, or may infer from the circumstances, using professional judgment, that the consumer does not object. A common example of the latter would be situations in which a family member or friend is invited by the consumer and present in the treatment room with the consumer and the provider when a disclosure is made.

“Where a consumer is not present or is incapacitated, a health care provider may share the consumer’s information with family [or] friends…, as long as the health care provider determines, based on professional judgment, that doing so is in the best interests of the consumer. Note that, when someone other than a friend or family member is involved, the health care provider must be reasonably sure that the consumer asked the person to be involved in his or her care or payment for care.

…

“For example, if the consumer does not object:

o A psychiatrist may discuss the drugs a consumer needs to take with the consumer’s sister who is present with the consumer at a mental health care appointment.

o A therapist may give information to a consumer’s spouse about warning signs that may signal a developing emergency.

BUT:

o A nurse may not discuss a consumer’s mental health condition with the consumer’s brother after the consumer has stated she does not want her family to know about her condition.

“In all cases, the health care provider may share or discuss only the information that the person involved needs to know about the consumer’s care or payment for care. See 45 CFR 164.510(b). Finally, it is important to remember that other applicable law (e.g., State confidentiality statutes) or professional ethics may impose stricter limitations on sharing personal health information, particularly where the information relates to a consumer’s mental health.”

3. What options do family members or friends involved in the care of an adult consumer with mental illness have if they are concerned about the consumer’s mental health and the consumer refuses to agree to let a health care provider share information with them?

The provision at issue is 45 CFR 164.512(j):

(j) Standard: Uses and disclosures to avert a serious threat to health or safety—

(1) Permitted disclosures. A covered entity may, consistent with applicable law and standards of ethical conduct, use or disclose protected health information, if the covered entity, in good faith, believes the use or disclosure:

(A) Is necessary to prevent or lessen a serious and imminent threat to the health or safety of a person or the public; and

(B) Is to a person or persons reasonably able to prevent or lessen the threat, including the target of the threat; or

(ii) Is necessary for law enforcement authorities to identify or apprehend an individual:

(A) Because of a statement by an individual admitting participation in a violent crime that the covered entity reasonably believes may have caused serious physical harm to the victim; or

(B) Where it appears from all the circumstances that the individual has escaped from a correctional institution or from lawful custody, as those terms are defined in § 164.501.

(2) Use or disclosure not permitted. A use or disclosure pursuant to paragraph (j)(1)(ii)(A) of this section may not be made if the information described in paragraph (j)(1)(ii)(A) of this section is learned by the covered entity:

(i) In the course of treatment to affect the propensity to commit the criminal conduct that is the basis for the disclosure under paragraph (j)(1)(ii)(A) of this section, or counseling or therapy; or

(ii) Through a request by the individual to initiate or to be referred for the treatment, counseling, or therapy described in paragraph (j)(2)(i) of this section.

The Guidance focuses on family members, but the provision applies to anyone able to help to prevent or lessen a serious and imminent threat to the health or safety of a person or the public. The Guidance adds the important qualification that information can be and should be freely received. It is only the disclosure of information that is restricted by HIPAA:

“The HIPAA Privacy Rule permits a health care provider to disclose information to the family members of an adult consumer who has capacity and indicates that he or she does not want the disclosure made, only to the extent that the provider perceives a serious and imminent threat to the health or safety of the consumer or others and the family members are in a position to lessen the threat. Otherwise, under HIPAA, the provider must respect the wishes of the adult consumer who objects to the disclosure. However, HIPAA in no way prevents health care providers from listening to family members or [friends]…, so the health care provider can factor that information into the consumer’s care.”

4. Can family- or friend-provided information be kept confidential?

“In the event that the consumer later requests access to the health record, any information disclosed to the provider by another person who is not a health care provider that was given under a promise of confidentiality (such as that shared by a concerned family member [or friend]), may be withheld from the consumer if the disclosure would be reasonably likely to reveal the source of the information. 45 CFR 164.524(a)(2)(v). This exception to the consumer’s right of access to protected health information gives family members [and friends] the ability to disclose relevant safety information with health care providers without fear of disrupting the family’s [or friend’s] relationship with the consumer.”

5. If a health care provider knows that a consumer with a serious mental illness has stopped taking a prescribed medication, can the provider tell the consumer’s family members or friends?

“So long as the consumer does not object, HIPAA allows the provider to share or discuss a consumer’s mental health information with the consumer’s family members [or friends]. See 45 CFR 164.510(b). If the provider believes, based on professional judgment, that the consumer does not have the capacity to agree or object to sharing the information at that time, and that sharing the information would be in the consumer’s best interests, the provider may [disclose the information to] the consumer’s family member[s or friends]. In either case, the health care provider may share or discuss only the information that the family member [or friend] involved needs to know about the consumer’s care or payment for care.”

6. When does mental illness or another mental condition constitute incapacity under HIPAA? For example, what if a consumer who is experiencing temporary psychosis or is intoxicated does not have the capacity to agree or object to a health care provider sharing information with a family member, but the provider believes the disclosure is in the consumer’s best interests?

“Section 164.510(b)(3) of the HIPAA Privacy Rule permits a health care provider, when a consumer is not present or is unable to agree or object to a disclosure due to incapacity or [in] emergency circumstances, to determine whether disclosing a consumer’s information to the consumer’s family, friends, or other persons involved in the consumer’s care or payment for care, is in the best interests of the consumer. Where a provider determines that such a disclosure is in the consumer’s best interests, the provider would be permitted to disclose only the [information] that is directly relevant to the person’s involvement in the consumer’s care or payment for care.” [MHA believes that, in the absence of a power of attorney or advance directive, which should be encouraged, it is preferable to appoint a legal guardian to make decisions concerning release of confidential information for consumers who are legally incompetent to do so. This cannot be required in emergencies, when the health care provider must act on its own assessment in the interest of integrated care.]

“This permission clearly applies where a consumer is unconscious. However, there may be additional situations in which a health care provider believes, based on professional judgment, that the consumer does not have the capacity to agree or object to the sharing of personal health information at a particular time and that sharing the information is in the best interests of the consumer at that time. These may include circumstances in which a consumer is suffering from temporary psychosis or is under the influence of drugs or alcohol. If, for example, the provider believes the consumer cannot meaningfully agree or object to the sharing of the consumer’s information with family, friends, or other persons involved in their care due to her current mental state, the provider is allowed to discuss the consumer’s condition or treatment with a family member, if the provider believes it would be in the consumer’s best interests. In making this determination about the consumer’s best interests, the provider should take into account the consumer’s prior expressed preferences regarding disclosures of their information, if any, as well as the circumstances of the current situation. Once the consumer regains the capacity to make these choices for herself, the provider should offer the consumer the opportunity to agree or object to any future sharing of her information.”

[MHA particularly approves of the use of the consumer’s prior expressed preferences regarding disclosures of their information as a guide, and asking again when decisional capacity is increased, since incapacity is usually not a global or permanent condition. A power of attorney or advance directive is the best way to preserve the consumer’s preferences.]

7. Does HIPAA permit a doctor to contact a consumer’s family or law enforcement if the doctor believes that the consumer might hurt herself or someone else?

As with paragraph 3 above, the provisions of 45 CFR 164.512 (j), quoted there, are dispositive. The Guidance adds:

“Yes. The Privacy Rule permits a health care provider to disclose necessary information about a consumer to law enforcement, family members of the consumer, or other persons, when the provider believes the consumer presents a serious and imminent threat to self or others.

Specifically, when a health care provider believes in good faith that such a warning is necessary to prevent or lessen a serious and imminent threat to the health or safety of the consumer or others, the Privacy Rule allows the provider, consistent with applicable law and standards of ethical conduct, to alert those persons whom the provider believes are reasonably able to prevent or lessen the threat. These provisions may be found in the Privacy Rule at 45 CFR § 164.512(j).

Under these provisions, a health care provider may disclose consumer information, including information from mental health records, if necessary, to law enforcement, family members of the consumer, or any other persons who may reasonably be able to prevent or lessen the risk of harm. For example, if a mental health professional has a consumer who has made a credible threat to inflict serious and imminent bodily harm on one or more persons, HIPAA permits the mental health professional to alert the police, a parent or other family member, school administrators or campus police, and others who may be able to intervene to avert harm from the threat.

In addition to professional ethical standards, most States have laws and/or court decisions which address, and in many instances require, disclosure of consumer information to prevent or lessen the risk of harm. Providers should consult the laws applicable to their profession in the States where they practice, as well as 42 USC 290dd-2 and 42 CFR Part 2 under Federal law (governing the disclosure of alcohol and drug abuse treatment records) to understand their duties and authority in situations where they have information indicating a threat to public safety. Note that, where a provider is not subject to such State laws or other ethical standards, the HIPAA permission still would allow disclosures for these purposes to the extent the other conditions of the permission are met.”

DUTY TO WARN. MHA calls attention to the need to assess the health care provider’s responsibilities under the “duty to warn,” referred to indirectly in this paragraph of the Guidance. A health care provider’s “duty to warn” generally is derived from and defined by standards of ethical conduct and state laws and court decisions such as Tarasoff v. The Regents of the University of California.[6] The duty to warn is a doctrine of tort liability that has been enacted into state law in different forms in 46 states plus the District of Columbia, either requiring or allowing disclosure of the confidences of a mental health consumer where the person has communicated to the psychotherapist a serious threat of imminent physical violence against a reasonably identified victim, who then either must or may be warned, depending on state law. State laws typically also require notification of law enforcement. HIPAA treats such a warning as an exception to its protection of consumer privacy. MHA is concerned that the duty to warn may inhibit access to and efficacy of treatment, depending on its formulation and implementation, but has not taken a position for or against it.

As restated in the Guidance, “HIPAA permits a covered health care provider to notify a consumer’s family members of a serious and imminent threat to the health or safety of the consumer or others if those family members are in a position to lessen or avert the threat. Thus, to the extent that a provider determines that there is a serious and imminent threat of a consumer physically harming self or others, HIPAA would permit the provider to warn the appropriate person(s) of the threat, consistent with his or her professional ethical obligations and State law requirements. See 45 CFR 164.512(j). In addition, even where danger is not imminent, HIPAA permits a covered provider to communicate with a consumer’s family members, or others involved in the consumer’s care, to be on watch or ensure compliance with medication regimens, as long as the consumer has been provided an opportunity to agree or object to the disclosure and no objection has been made. See 45 CFR 164.510(b)(2).”

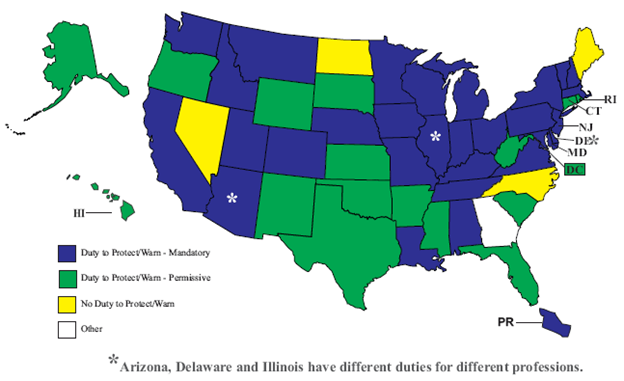

State legislation codifying the duty to warn has been enacted in many states. The most detailed summary is a twelve-year-old article, “Tarasoff at 25.”[7] As of that year, 27 states imposed a duty to warn an identified potential target of violence. Another 10 jurisdictions (9 states, plus the District of Columbia) accorded psychotherapists permission to warn. The remaining 15 jurisdictions (14 states, plus federal law) had no definitive law on the issue. A 2013 summary by the National Conference of State Legislatures[8] gives more up-to-date information and precise statutory language: As of 2013, there were 30 duty to warn states, 17 permission to warn jurisdictions (15 states, plus DC, plus one state, GA, where permission is granted by a non-binding rule only), and 5 jurisdictions with no definitive law on the issue (4 states, plus the federal government):

As these laws may change at any time, this map may not be current.

As stated by Herbert and Young, “Tarasoff and its statutory and case law progeny, as a practical matter, distill down to a duty to warn, where it exists, in essentially two situations. One is where the therapist believes the [consumer] is not a danger to himself (or herself or others) or is not mentally ill—hence, not committable [, or the mental health system lacks the resources to respond] —but he (or she) has made a threat to harm another (or, in some jurisdictions, a suicide threat). This would occur either in discharging an inpatient or in electing not to hospitalize an outpatient—that is, in the case of a decision not to contain the [consumer]. The second situation arises from inability to contain the [consumer], such as when an outpatient phones in a threat or an inpatient elopes [leaves against medical advice].”[9]

New York enacted a controversial 2013 law that significantly expanded upon the Tarasoff principle by eliminating the requirement that the identified threat of serious harm be “imminent.”[10] State and federal laws as well as generally accepted psychiatric practice recognize that a breach of patient confidentiality may be necessary to prevent harm to self or others, but only when the risk posed is both serious and imminent.[11] OCR (the Office for Civil Rights, the enforcement arm of the HHS General Counsel’s Office) is now examining whether the new law complies with HIPAA. Under HIPAA, a disclosure to mitigate a threat to health or safety may be made without patient authorization only if the threat is both serious and imminent and is made to law enforcement or to a potential target, elements that are missing from New York’s SAFE Act.

Call to Action

MHA affiliates and other advocates should monitor health care providers’ compliance with HIPAA privacy standards including the Guidance and assure that they take up-to-date, reasonable precautionary measures when engaging in electronic maintenance or transmission of health information.

Affiliates and advocates should advocate for appropriate state legislation or other action concerning:

- Medical Emergencies. Information should be freely available to licensed health care personnel for the purpose of treating a condition that poses an immediate threat to the health of the consumer or others.

- Minors. Involvement of children, youth and their families in their care is helpful in determining appropriate treatment, and explicit consent of the minor can be equally helpful even if not legally required. Therefore, the signatures of both the minor and a parent/guardian should be sought once the consumer is able to read and write, and states should consider requiring consent of older, functionally emancipated minors.

- Court Orders. Courts may authorize disclosure of confidential information for “good cause,” as delineated in statutes and in court rules and procedures. For court orders authorizing disclosure for other than criminal purposes, HIPAA requires that the consumer receive formal notice of the request and an opportunity to respond but does not set a standard, which is left to state law. MHA advocates that the judge weigh the need for disclosure against the potential harm to the consumer and to the clinician-consumer relationship and its impact on the treatment process. HIPAA requires that the order limit disclosure to information essential to the demonstrated purpose and provide protection against future public scrutiny, such as by sealing court records. 45 CFR 164.512 (e) requires a qualified protective order that: (A) Prohibits the parties from using or disclosing the protected health information for any purpose other than the litigation or proceeding for which such information was requested; and (B) Requires the return to the covered entity or destruction of the protected health information (including all copies made) at the end of the litigation or proceeding.

- Psychiatric Advance Directives. Individuals should have the right to release HIPAA-protected information to their designated health care proxies and in their psychiatric advance directives, and should routinely do so. State law presumptions could help consumers to avoid HIPAA impediments to sharing information as they wish.

- Super-Confidential Information. The federal government and some states have identified information that should be MORE PROTECTED than other information covered by HIPAA. MHA generally opposes special protections of this kind because there is no evidence that additional formalities actually increase privacy, and such special protections compromise integration of care. Examples of “super-confidential” information include: genetic information and information pertaining to school records, substance abuse, mental health conditions, HIV testing, and sexually transmitted diseases, as defined and protected by specific federal and state laws and regulations. MHA does support the HIPAA exemption for psychotherapy notes, as defined in 45 CFR 164.501.

- Duty to Warn. Affiliates and advocates will want to follow developments in other states, like New York, to assess the efficacy of duty to warn statutes in preventing violence and to weigh the effect of reduced confidentiality, candor and trust on outreach, treatment, and recovery.

- HIPAA Enforcement. MHA encourages affiliates to relay complaints to OCR. HIPAA enforcement has dramatically increased since the passage of the HITECH Act in 2009, with $14,883,345 in penalties and settlements through 2013. HHS issued new regulations in January 2013, implementing the HITECH Act’s HIPAA modifications. According to OCR Director Leon Rodriguez, the rule “marks the most sweeping changes to the HIPAA Privacy and Security Rules since they were first implemented.” One of the most notable changes was expanding HIPAA to be directly applicable to business associates. This is significant because 20% of the HHS “Hall of Shame” violations were by contractors, equating to over 12 million consumers who have had their information placed at risk due to an organization outside of the healthcare organization itself, and outsourcing is increasing.[12] MHA will monitor OCR’s enforcement of its 2014 Guidance, quoted above, which demonstrates its interest in mental health privacy issues.

Effective Period

The Mental Health America Board of Directors approved this policy on December 6, 2014. It will remain in effect for five (5) years and is reviewed as required by the Public Policy Committee.

Expiration: December 31, 2019

[1] P.L. 104-191, 110 Stat.1936 (1996), 29 U.S.C. §1181, 42 U.S.C. §1320, 1395, and associated rulemaking by the Department of Health and Human Services, 45 C.F.R. §§160-164. HIPAA enforcement was substantially strengthened by the passage of the HITECH Act, Public Law 111–5, 123 Stat. 115 (2009), and sections within 45 CFR part 160 finalized in 2013 that relate to the authority of the Secretary of the HHS to impose civil penalties under Section 1176 of the Social Security Act, 42 U.S.C. 1320d–5.

[2] a summary of which can be found at http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/understanding/summary/index.html

[4] Although the Guidance is focused on mental health, it is important to remember that the standards apply to all health records, and MHA strongly supports uniform standards in the interest of promoting integrated care.

[5] The Helping Families In Mental Health Crisis Act of 2013, H. R. 3717; Hilt, R.J. “HIPAA: Still Misunderstood after all of these Years,” Pediatric Annals 43:240 (2014).

[6] Tarasoff v.The Regents of the University of California, 551 P.2d 334 (Cal.1976)

[7] Herbert, P.B. & Young, K.A., “Tarasoff at 25,” Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 30:275–281(2002). http://focus.psychiatryonline.org/data/Journals/FOCUS/2597/376.pdf

[9] Id.

[10] New York Secure Ammunition and Firearms Enforcement Act of 2013 (NY SAFE Act) and Section 9.46 of the NY Mental Health Law, http://www.omh.ny.gov/omhweb/safe_act/ .

[11] New York State Psychiatric Association, “The SAFE Act, Guidelines for Complying with the New Mental Health Reporting Requirement,” published online at http://www.nyspsych.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=73:the-safe-act--guidelines-for-complying&catid=41:safe-act&Itemid=140

[12] Entire paragraph: See Solove, D.J., “HIPAA Turns 10: Analyzing the Past, Present, and Future Impact, 84 Journal of AHIMA 22 (2013), http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2245022

this page